Photo credit: Maciej Btedowski © 123RF.com

Thurston County in Washington State has developed a systemic safety analysis approach that can be used by locations with low-crash density and provide Thurston County with a proactive, data-driven, and defensible method of identifying projects eligible for WSDOT HSIP funding.

Washington State has adopted the Target Zero program—with the goal to reduce traffic fatalities and serious injuries on Washington’s roadways to zero by the year 2030 (Washington Traffic Safety Commission [WTSC], 2016). As part of this initiative WSDOT dedicates approximately 70% of HSIP funding to local safety projects. Since 2010, WSDOT has awarded more than $170 million in HSIP funding to local agencies. However, to qualify for funding, agencies must show that the candidate projects were identified through a data-driven process (WTSC, 2016).

Thurston County decided to proactively reduce the number of annual, severe crashes on Thurston County’s 1,000-mile system (an average of 35 crashes per year based on 2006 to 2010 data [Davis, 2016, pers. comm.]). Thurston County’s primary challenge was identifying an analytical process that identified the low density of severe crashes typical of rural, local systems (0.035 severe crashes per mile per year [Davis, 2016, pers. comm.]).

Thurston County’s initial analysis found no severe crashes at locations meeting WSDOT’s high-crash definition and concluded that the traditional site analysis approach could not identify candidate projects for safety funding or support the safety project development process. To address issues associated with reporting low density of severe crashes, Thurston County followed the systemic safety analysis approach, described in the U.S. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)’s Systemic Safety Project Selection Tool (FHWA, 2013). This approach provided the County with a proactive, data-driven, and defensible method of identifying projects eligible for WSDOT HSIP funds (Figure 11-1).

Using the systemic approach, Thurston County analyzed 5 years of crash data and found that 58% of severe crashes in the County were classified as road departure—compared to an average of 38% for the state system (Davis, 2016, pers. comm.). The results of the systemic analysis identified locations with the greatest potential for crash reduction and also identified two key characteristics of severe road departure crashes (Davis, 2016, pers. comm.):

This analysis also identified a group of roadway and traffic characteristics over-represented at crash locations, including:

These characteristics—common at locations with a crash history—were used as systemic factors to conduct the assessment of the 337-mile arterial/collector system and to identify candidate locations for improvements with similar characteristics from more than 270 signed horizontal curves (Davis, 2016, pers. comm.). In addition, the characteristics determined the prioritization and selection of low-cost countermeasures—including enhanced edge delineation, new/upgraded warning signs, shoulder and center rumble strips, and new/upgraded guardrails.

Thurston County used the analysis findings to identify and prioritize the following safety projects (Davis, 2016, pers. comm.):

Using skills acquired during training to become a best practices manager in highway safety, Thurston County’s engineer Scott Davis identified and prioritized a list of safety projects totaling more than $4 million. The County received HSIP funding from WSDOT for all submitted safety projects. Thurston County has implemented these projects and is conducting a follow-up evaluation to determine the level of crash reduction resulting from the riskbased, proactive deployment of low-cost countermeasures.

The County has since used the systemic safety process to identify three potential high friction surface treatment project locations and address speeding-related concerns by identifying candidate corridors for speed feedback sign deployment.

These efforts are a model for Washington State where 31 of its 39 counties have developed data-driven county road safety plans to obtain HSIP funding. In 2014, WSDOT awarded Thurston County HSIP funding to update the systemic study and create a countywide traffic safety plan to guide future HSIP safety investments (Davis, 2016, pers. comm.).

Scott Davis

Thurston County, Washington

(360) 867-2345

davissa@co.thurston.wa.us

Thurston County successfully addressed the issue of high-crash density using a systemic, data-driven process. To incorporate this approach into crash analysis a local agency could:

Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) streamlined the environmental documentation process for low-cost safety countermeasures designed for minimal environmental impacts, including:

These countermeasures do not require reconstruction and are typically confined to the existing roadway. If outside the road edge, they do not require grading. Even though the list of project types is short, it represents the majority of projects proposed by local agencies for implementation through the state’s HSIP.

The first step of the streamlined process is developing a one-page (two sided) spreadsheet—the Environmental Documentation for Federal Projects with Minor Impacts (Appendix D). This form is completed by local agency staff and includes such basic information as:

The local agency engineer signs the completed form and sends it to MnDOT’s Division of State Aid for Local Transportation for review and approval (Refer to Appendix D). This form also is online at (MnDOT, 2017):

http://www.dot.state.mn.us/stateaid/environmental-forms.html.

After selecting local project applications for funding through the HSIP, the Division of State Aid assembles a comprehensive list of proposed improvement projects across all local agencies and forwards this list to MnDOT’s Office of Environmental Stewardship to review for possible impacts on Historic Properties and Endangered Species. Once there is confirmation of no impact, MnDOT, acting on behalf of the U.S. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), makes a Determination of No Effect for each project on the list (Appendix E). The majority of projects that pass review are cleared for further project development and implementation. In certain instances, projects that pass review may be subject to further study.

When local agencies focus on low-cost safety strategies that do not require regrading or reconstruction, they can obtain environmental clearance for project implementation with minimum effort.

Gary Reihl

Minnesota Department of Transportation

(651) 366-3819

MnDOT successfully streamlined the environmental documentation process for low-cost safety countermeasures. To develop a single-review process, a local agency could:

To help local agencies comply with FHWA guidelines and taking into account the need for cost and time efficiencies given agencies’ limited/finite resources, Minnesota DOT (MnDOT) decided to bundle local agency projects collectively by district. Each MnDOT district created one single project containing numerous safety improvements to local roads. This has led to reduced complexity and paperwork. MnDOT has contacted county engineers to share experiences, workloads, and materials with other local agencies to promote more efficient and cost-effective projects.

The bundling approach has been successful in implementing HSIP-funded projects across Minnesota. Examples include (Tasa, 2017, pers. comm):

This approach has also resulted in the following cost savings (Tasa, 2017, pers. comm):

Even though the bundling approach was successful overall, MnDOT identified three potential barriers to implementing bundled projects. Barriers and solutions are as follows.

Solution: MnDOT developed safety plans in every Minnesota county to document the systemic risk assessment of county facilities (Case Study 10 in this Manual). These plans included a comprehensive list of suggested safety improvements and corresponding project forms that could be submitted by counties during the HSIP solicitation process. This enables county engineers to discuss multicounty safety projects with their peers.

Solution: MnDOT’s state aid staff developed a process that assigned responsibility to a lead county for administering the contract, paying the contractor, and working with participating counties.

Solution: MnDOT developed an interagency agreement describing the working arrangements between agencies:

Appendix F provides an example of an interagency agreement. This first multicounty project plan can be used as a guide by county engineers.

Rick West

Otter Tail County, Minnesota

(218) 998-8470

Lou Tasa

Minnesota Department of Transportation, District 2

(218) 755-6570

MnDOT successfully developed a bundling process involving multicounty participation that reduces documentation and streamlines processes for easier HSIP delivery. To develop a streamlined process, a local agency could:

In fiscal year (FY) 2013, the New Jersey Transportation Planning Authority (NJTPA) created the Local Safety Engineering Assistance Program (LSEAP) to help implement projects administered under the Local Safety Program (LSP) and High Risk Rural Roads Program (HRRRP) (NJTPA, 2013). The LSEAP provides design assistance through plans, specifications, and cost estimates (PS&Es). In order to make LSEAP viable, the New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT) increased funding for authorizations from $2.8 million in FY 2013 (when LSEAP was implemented) to an average of $17 million per year for FYs 2014-2016 (Figure 14-1). Details on the LSP and HRRRP are online at (NJTPA, 2017): https://www.njtpa.org/LSP.aspx.

Under the LSEAP, consultants are co-managed by the NJTPA and sub-regions. Consultant contracts are HSIP-funded; NJTPA administers these contracts and provides project oversight. Each project sponsor is responsible for technical direction, supervision, and reviews the development of the project’s PS&Es. The scope of work for the consultant contracts includes survey, right-of-way, engineering, design, and the necessary permitting services to prepare PS&Es.

Projects are divided into preliminary engineering and final design phases. Funds for preliminary engineering are released when the contracts are executed. Preliminary engineering plans and environmental documents are submitted to NJDOT Bureau of Programmatic Resources, which reviews and approves project Categorical Exclusion Documents (CEDs). Once the CEDs are approved, NJTPA authorizes the final design phase and the consultant prepares the full PS&E package. PS&Es are submitted to NJDOT Local Aid for review and federal construction authorization is requested.

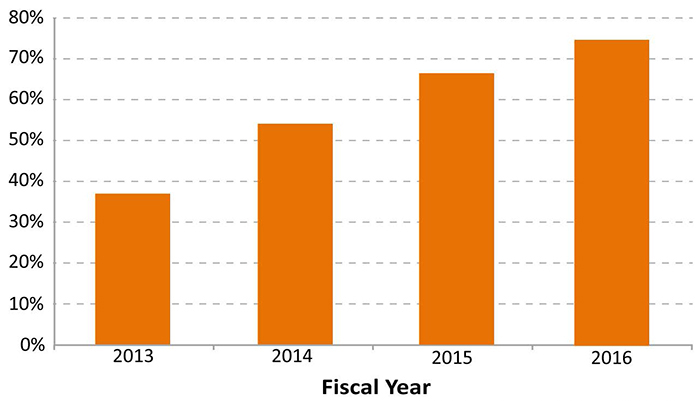

Table 14-1 summarizes the LSEAP and Figure 14-2 shows the percentage of projects requesting design assistance by fiscal year. The percentage of projects has grown from 38% requesting assistance in FY 2013 to 75% requesting assistance in FY 2016.

Table 14-1. Annual Summary of Local Safety Engineering Assistance Program (New Jersey)

| Construction Authorizations | Design Costs | # of projects in design | Total # of projects selected for the program year | % of total projects requesting design assistance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY 2013 | $2,816,000 | $462,294 | 5 | 13 | 38% |

| FY 2014 | $16,328,484 | $1,332,811 | 8 | 15 | 53% |

| FY 2015 | $18,288,233 | $2,805,863 | 12 | 18 | 67% |

| FY 2016 | $19,650,000 | $4,474,771 | 16 | 22 | 75% |

Source: (Mittman, 2017, pers. comm)

Figure 14-2. Percentage of Projects Requesting Design Assistance by Fiscal Year (New Jersey)

Source: (Mittman, 2017, pers. comm.); Adapted by FHWA

Christine Mittman

North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority

(973) 639-8448

North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority

(973) 639-8400

NJTPA successfully created a local agency assistance program to help advance projects selected under the LSP and HRRRP and prepare construction documents. To develop a similar program, local agencies could:

Minnesota and North Dakota committed to support local system safety projects by dedicating federal safety funding from their states’ Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP). Each state dedicates a portion of its HSIP funding for local system projects to address severe crashes (involving fatalities plus incapacitating injuries) that occur on local systems. The funding designated for local systems is set aside so that local agencies are only competing with each other, and not competing with the state system for the same allotment of funding.

In 2011, Minnesota DOT (MnDOT) first set aside HSIP funding for local system safety improvements. Since then, MnDOT has committed more than $80 million of HSIP funding, which has benefitted many of the state’s 87 counties. Between 2011 and 2016, approximately 300 local system safety projects were funded by HSIP and 85% of the counties have implemented at least 1 HSIP-funded project. Most projects incorporated 1 or more of the following safety improvements (Devoe, 2016, pers. comm.):

MnDOT indicates that establishing the set aside and corresponding safety improvements has resulted in an approximate 25% reduction in the number of county traffic fatalities (Devoe, 2016, pers. comm.).

Crow Wing County has implemented more than 12 HSIP-funded safety projects totaling approximately $1.5 million. These 12 projects have included $1 million for 162 miles of enhanced 6-inch grooved-in edge lines, $0.3 million for 389 miles of enhanced curve warning signs, and $0.2 million for street lighting at 31 rural intersections (Bray, 2016, pers. comm.).

Table 15-1. MnDOT HSIP Funding for Local System Safety Projects 2011 to 2016

| Greater Minnesota Counties | GMC* | Metro | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segments | Curves | Intersections | Total | Total | |||||||

| Enhance Marking | Edge Line Rumbles | Total | Lights | Signs | Dynamic Warning | Total | |||||

| 2011 | $0.8 | $2.8 | $3.6 | $0.5 | $0.7 | 0 | 0 | $0.7 | $4.8 | $5.8 | $10.6 |

| 2012 | $1.6 | $0.8 | $2.4 | $0.9 | $0.9 | $0.1 | 0 | $1.0 | $4.3 | $5.2 | $9.5 |

| 2013 | $1.8 | $1.0 | $2.8 | $0.6 | $1.7 | $0.1 | 0 | $1.8 | $5.2 | $2.9 | $8.1 |

| 2014 | $4.9 | $3.8 | $8.7 | $3.1 | $0.5 | $0.1 | $1.2 | $1.8 | $13.6 | $6.2 | $19.8 |

| 2015 | $2.8 | $5.7 | $8.5 | $1.3 | $1.0 | $0.5 | $1.5 | $3.0 | $12.8 | $2.7 | $15.5 |

| 2016 | $3.9 | $6.6 | $10.5 | $0.4 | $0.3 | 0 | $1.6 | $1.9 | $12.8 | $6.8 | $19.6 |

| Total | $15.8 | $20.7 | $36.5 | $6.8 | $5.1 | $0.8 | $4.3 | $10.2 | $53.5 | $29.6 | $83.1 |

Notes:

Costs are represented in millions of U.S. dollars.

*GMC = Greater Minnesota County

Source: (Devoe, 2016, pers. comm)

Table 15-2. NDDOT HSIP Funding

for Local System Safety Projects 2017 to 2020

| HSIP Summary | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total | |

| State | $11.42 | $3.8 | $2.1 | $1.8 | $19 |

| City | $2.3 | $0.2 | 0 | 0 | $2.5 |

| County | $0.2 | $2.1 | $0.7 | 0 | $3.0 |

| Tribal | $0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | $0.8 |

| Local Subtotal | $3.3 | $2.3 | $0.7 | 0 | $6.3 |

| Total | $7.5 | $6.1 | $2.8 | $1.8 | $18.3 |

Costs are represented in millions of U.S. dollars.

Source: (Devoe, 2016, pers. comm)

Crow Wing County also completed a follow-up study of these projects to document effectiveness. The county found that road departure crashes along the segments with enhanced edge lines decreased by 58% and crashes in the curves with the enhanced warning signs (chevrons) decreased 34% (Bray, 2016, pers. comm.). The County also found the crash reduction at the lighted rural intersections was small (possibly due to the relatively small number of crashes in the previous period), but also noted two unexpected complimentary benefits (Table 15-1).

North Dakota Department of Transportation (NDDOT) developed its Local Road Safety Program in 2015 and, like MnDOT, committed to earmarking part of its HSIP for implementing local system safety improvements. The Fiscal Year (FY) 2017 to FY 2020 HSIP includes participation by 18 counties, 3 cities, and 2 tribes (Table 15-2) (Kuntz, 2016, pers. comm.).

Eric Devoe

Minnesota Department of Transportation

(651) 234-7016

eric.devoe@state.mn.us

Shawn Kuntz

North Dakota Department of Transportation

(701) 328-2673

skuntz@nd.gov

Tim Bray

Crow Wing County, Minnesota

(218) 824-1110

tim.bray@crowwing.co.mn.us

The 30 programmed safety projects on the local system are valued at approximately $6.3 million—$2.5 million for city projects, $3 million for county projects, and $0.8 million for tribal projects. These projects are the result of a data-driven analytical process and use effective, low-cost safety countermeasures including:

MnDOT and NDDOT successfully committed to support local system safety projects by using federal safety funding from the state’s HSIP. To support local system safety projects, a local agency could:

Local road safety improvements are emphasized in Ohio’s Strategic Highway Safety Plan (SHSP) and in the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP). The Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) spends about $102 million each year on improving high-crash and severe-crash locations on local roads.

ODOT also works with local partners to fund investments that improve safety on Ohio roads (ODOT, 2017). ODOT collaborates with the Local Technical Assistance Program (LTAP), the County Engineers Association of Ohio (CEAO), metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), and local governments and agencies to comprehensively expand training, technical assistance, and funding opportunities to local partners. These collaborative relationships have evolved into resources that can help local agencies when applying for federal HSIP funding:

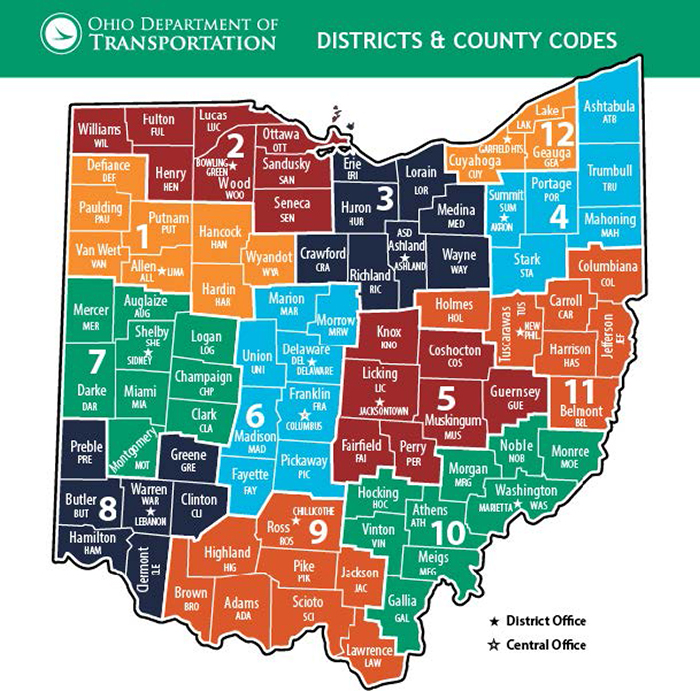

ODOT’s district offices facilitate discussions with local governments and agencies about safety program planning and development. In each district, a dedicated Highway Safety Coordinator is the liaison between local agencies and department staff and helps agencies navigate the HSIP process. ODOT has 12 district offices and one central office (Figure 16-1) with planning and engineering staff at each District office (ODOT, 2014), allowing ODOT district staff to develop close working relationships with local agencies. District staff are also encouraged to participate in local government meetings, including (ODOT, 2014):

The ODOT district safety coordinator is the first point of contact and works directly with local officials to develop projects using the statewide planning process. Local agencies applying for HSIP funding can use their ODOT district office for HSIP application assistance (ODOT, 2014).

Requests for low-cost safety improvements may qualify for an abbreviated application, allowing a shorter, more cost-efficient study to be conducted instead of a more detailed and costly formal study (ODOT, 2017b). HSIP applications are reviewed by the local district office before they are submitted to the central office, where they are reviewed by a multidiscipline committee.

Figure 16-1. ODOT District and Central Offices

Source: ODOT, 2017c

The Ohio Highway Safety Improvement Program 2016 Annual Report describes the HSIP application process (OH, 2016).

“A multi-discipline committee at ODOT headquarters reviews all applications and supporting safety studies. The committee can approve a proposal, select a different safety strategy, or request further study before allocating money. ODOT spends approximately $85 million dollars in safety funds annually through this program. Once funding is secured, safety projects are scheduled for construction. How quickly projects proceed to construction depends on the available funding and complexity of the project. Short-term, low-cost projects can be implemented within a few months. Other projects that require environmental mitigation, complex engineering design and/or utility and right of way relocation may take several years. In all cases, ODOT encourages sponsors to act as quickly as possible. Upon project completion, the department monitors locations to make sure the improvements are reducing crashes as designed.”

ODOT’s innovative partnerships with LTAP and ODOT, along with an emphasis on a data-driven analysis process, are instrumental in improving local road safety.

ODOT created the Statewide Steering Committee to share information/resources and create a central repository for distributing crash data and trends. The Committee includes representatives from local, state, and federal government agencies who have access to and share crash information with hundreds of other safety organizations across Ohio. Since crash data and many available crash analysis resources are centrally located, this statewide information strategy is the most effective way to implement strategies that address fatalities on Ohio roads. It informs local agencies, provides high-quality data without increasing costs, and helps increase local agency staff expertise on data analysis and crash trends (OH, 2016). Members of this Committee are also the primary contributors to and reviewers of ODOT’s SHSP.

ODOT publishes the Program Resource Guide (ODOT, 2017d), which documents available funding opportunities for local governments, transportation advocacy groups, planning organizations, and citizens. The Guide provides best practices for soliciting funding and locating points of contact when applying for funding and will “improve access to funding programs and resources and help continue the development of Ohio’s transportation infrastructure” (ODOT, 2017d).

ODOT consults with district offices and local communities in providing signal timing upgrades in areas with high intersection crashes and prioritizes upgrades in locations where crashes are linked to poor signal timing (ODOT, 2017e).

Each year, ODOT allocates $1 million under the Township Safety Sign Grant Program for safety signage upgrades, including signs (typically curves and intersection), posts, and applicable hardware (ODOT, 2017a). Townships can apply for up to $50,000 in funding if the Township:

ODOT partners with LTAP and CEAO to conduct safety audits as part of the HSIP-funded Roadway Safety Audit (RSA) Program. The RSA Program focuses on making improvements to roads where serious injuries and fatalities are higher than the state average.

Each year, members of the CEAO can request funding for safety upgrades on county-maintained roads. If applications are accepted, CEAO allocates a portion of its total $12 million CEAO safety set aside budget to the approved applicant for various road improvements. The applicant can then request additional HSIP funds from ODOT. ODOT prioritizes applications eligible for safety funding by funding match (such as a CEAO safety set aside).

The ODOT successfully developed a comprehensive range of resources to engage and encourage local agencies with varying levels of experience to participate in the HSIP. To develop similar partnerships, an agency could:

Derek Troyer

Ohio Department of Transportation

(614) 387-5164

derek.troyer@dot.ohio.gov

FHWA’s Minnesota Division partnered with Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) and Minnesota’s county engineers to develop a new project funding approach for the state that removes the maintenance funding barrier. This approach changes the classification for some projects typically classified as maintenance so they are eligible for HSIP funding. For example, U.S. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) had previously determined that the HSIP should not fund pavement markings on rehabilitation projects (Stein, 2017, pers. comm.). Under this new data-driven approach, maintenance costs of countermeasures with short design lives (such as pavement markings) would be classified as periodic refreshing (instead of maintenance) and considered eligible for HSIP funding, providing that:

The key to this new project funding approach is collaboration between the local agency, state DOT, and FHWA. The local agency conducts the systemic assessment, prepares a safety plan, and submits projects to state safety program managers for funding. The state DOT identifies statewide priorities and commits to including local agencies in the HSIP. FHWA provides technical oversight and funding support.

This partnership has resulted in several positive outcomes, including (Vizecky, 2017, pers. comm.):

Mark Vizecky

Minnesota Department of Transportation

(651) 366-3839

Will Stein

FHWA, Minnesota Division

(651) 291-6122

FHWA’s Minnesota Division successfully worked with MnDOT and local agencies to reclassify projects requiring HSIP funding. To participate in a similar program, other local agencies could:

RSPCB Program Point of Contact

Felix Delgado, FHWA Office of Safety

Felix.Delgado@dot.gov

FHWA Office of Safety

Staff and Primary Work Responsibilities

FHWA Office of Safety

Safety and Design Team

FHWA Resource Center